Back in 2000, when I first moved to the picturesque city of Victoria, BC, I met with a realtor to discuss buying a house. My plan was to buy what I could afford now, sell for a higher price down the road, and use the profits to upsize. This might sound like real estate 101 to us today, but at the time, my realtor balked at the idea of treating real estate as an investment. She was emphatic that “prices haven’t changed in over 20 years!” Between land taxes and relator fees, she insisted my plan was ultimately going to cost me in the long run. To her, homes were just for living in.

Being new to Victoria, I put my trust in her decades of experience and intimate knowledge of the Victoria real estate market and did not buy a home. Unbeknownst to me, that moment was almost the exact bottom of the market. Some houses valued between $150,000 to $250,000 in 2000 are now worth $1.75 million to $2.25 million today.

Hindsight is 20/20, but I have to say—this one hurt. Not just because I missed out on a massive return, but because I let one dissenting voice go against my gut instinct. Something I think many can relate to at one point or another in our lives, particularly investors.

Conversely, around the same time I was walking away from a million-dollar investment opportunity, many investors were running toward what they thought was their big break. Technology stocks were soaring. Crowd favourites like Qualcomm were driven up to excessive valuations, riding the momentum to new heights almost every day—and many investors did not want to miss the boat.

I still vividly remember the day in early 2000 when Qualcomm surged on strong earnings but closed at its low for the day, signaling the beginning of the end of the dot-com bubble. The NASDAQ composite index, which had risen 800% from 1995 to its peak in March 2000, fell nearly 80% from that peak by late 2002, wiping out all the gains during the bubble.

The psychology of a market cycle

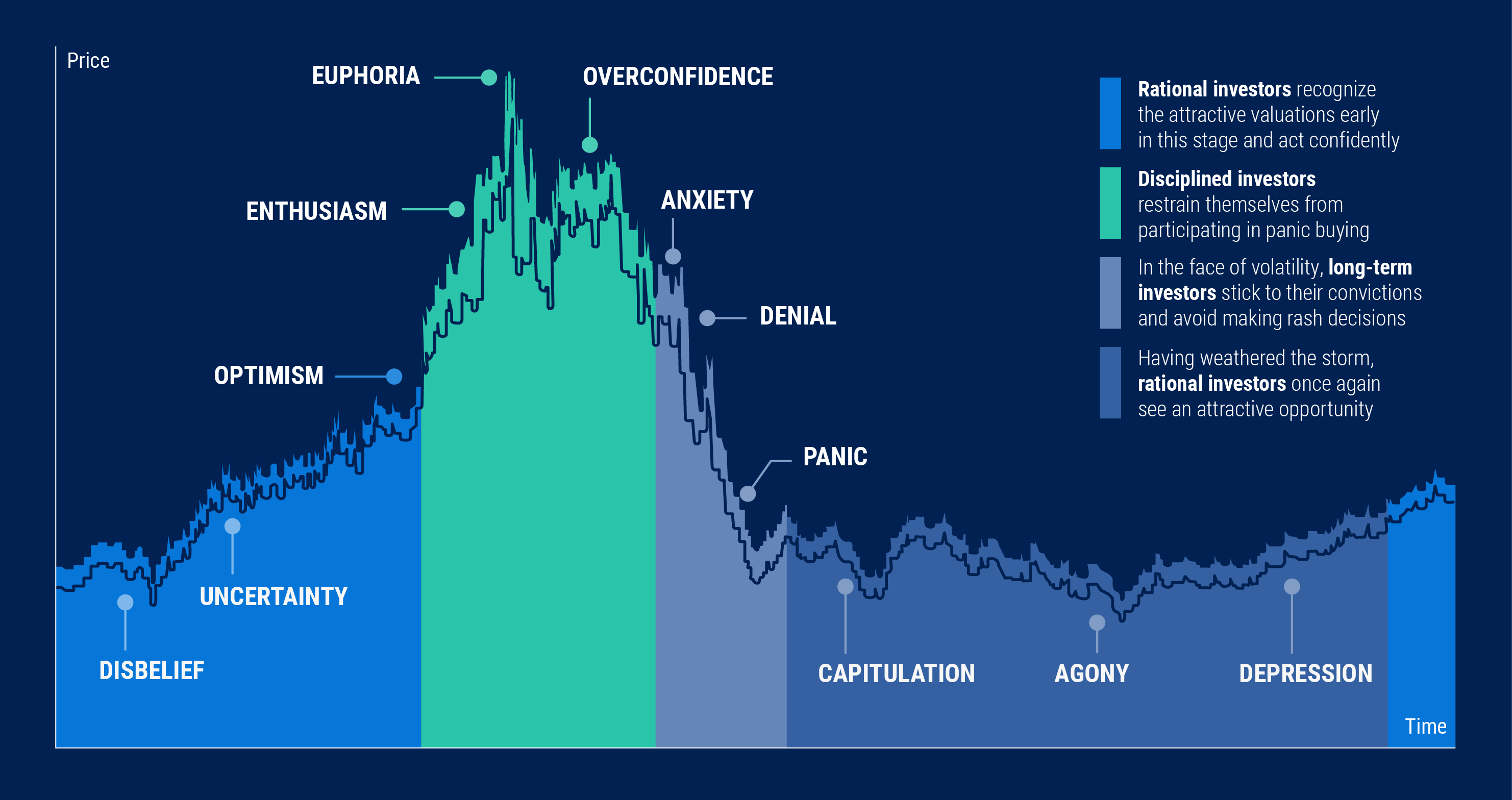

Any investor who has experienced a market cycle would be familiar with its psychological phases. Seasoned investors have likely felt the exhilarating highs of a bull market, where losing money seems impossible, and the depressive lows of a bear market, where recovery appears out of reach.

Let’s explore these phases to understand how a hypothetical stock market cycle might unfold.

In the initial phases of disbelief and uncertainty, “smart money” recognizes attractive valuations and begins to build their positions in anticipation of the upcoming bull market. Most inexperienced investors, perhaps still reeling from the previous downturn, adopt a wait-and-see approach, often missing the best entry prices. Rather than using low valuations as a signal, they wait for price recovery before jumping in.

As the bull market begins, optimism grows, fueling the rally and creating an upward cycle. During the phases of optimism and enthusiasm, everyone seems to be a market wizard. Almost no strategy loses money, and investors gain confidence. IPOs, mergers and acquisitions, and overall market activity increase significantly. While smart money remains invested to capitalize on market sentiment, it becomes more selective and cautious, gradually shifting to more defensive positions. Meanwhile, retail investors may pursue riskier strategies, even taking out loans to leverage returns.

For a time, everything seems to be going well. Companies IPO at higher prices, and valuations become stretched as good news abounds. Instead of considering risk, many investors chase opportunities, driven by the fear of missing out. In these final euphoric stages of a bull market, smart money begins to sell off and hedge their positions.

Then, potentially triggered by a negative catalyst like a geopolitical event or worsening macroeconomic conditions, sentiment deteriorates, and prices begin to drop significantly. Strategies that once seemed foolproof now only lose money. Anxiety sets in as investors deny the new reality, leading to increased volatility. The saying “markets take the stairs up and the elevator down” becomes a harsh reality as investors panic and rush to sell.

Selling begets more selling as volatility surges, margins are called, and the psychological toll of mounting losses becomes so severe that many capitulate, selling everything and vowing never to invest in stocks again. Even discussing investing in stocks becomes taboo, as it evokes painful memories of loss. However, with depressed prices and more reasonable valuations, opportunities for the next market cycle emerge, and the cycle starts anew.

Why does this keep happening?

As the saying goes, history doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes. So why do these cycles persist? One reason is that human nature remains constant. Each generation experiences the same fears, biases, and emotional reactions as the previous one, creating recurring patterns over the decades.

Moreover, because humans have finite lifespans, new generations tend to lose the wisdom and experiences of their predecessors. Those who have lived through market cycles are no longer around to remind them. Even if they were, the unfortunate reality is that truly learning a lesson often requires experiencing it firsthand rather than simply being told about it.

A more recent example can be seen in the U.S. stock market, which has effectively been in a bull market since the 2008-2009 financial crisis. While markets dipped sharply during the 2020 pandemic, the V-shaped recovery was swift, and investors hardly felt the pains of a true bear market. Consequently, younger investors, particularly those under the age of 35 to 40, have never personally endured a lengthy bear market that tested their emotional grit and endurance.

For instance, those who invested near the peak of the dot-com bubble had to wait a decade to break even if they bought the S&P 500 index, and a decade and a half if they bought the NASDAQ composite index. This historical example serves as a sobering reminder of the lengthy periods during which investors may see no returns, highlighting the importance of patience and understanding one’s risk tolerance.

How can investors protect themselves?

Is all this to say that investors should try to time the markets? Not at all. This serves as a reminder of the potential dangers of periods of excess and how the psychological effects of market swings can lead to poor decision-making.

Long-term buy-and-hold investors should not let market downturns dissuade them from pursuing attractive opportunities, even if sentiment is extremely negative and bad news dominates the headlines. The pain of seeing account balances decline day by day, week after week, and month after month can impose heavy psychological burdens, potentially leading to capitulation even among the most determined investors. All human beings are susceptible to herd mentality to some degree, and investors must be aware of that.

One thing’s for sure. Since moving to Victoria, I have bought numerous houses and never again relied solely on the advice of realtors or the people around me.

Keep an eye out for my next article where I’ll be discussing some of the advantages and disadvantages of various indicators that may help investors identify times of excess, such as the Warren Buffett Indicator, the volatility index, and more. Stay tuned!